The Diary

Introduction

This is a story about a war time diary written by a German soldier and the lives and hearts it touched.

It is a story about the German author of the diary who was forced to leave it in the Tunisian desert and the American soldier who found it.

When the American soldier takes possession of the diary he becomes the guardian of the words and sentiments written by the author.

The diary was in possession of the author for nearly two years and traveled many miles in the german theatre of operations in North Africa (1942-1943).

The Guardian found the diary at a battle site in Tunisia in 1943 as Afrika Korps troops retreat from the advance of allied forces.

Their lives were never closer than the day the diary changed hands despite the fervent hope of the guardian to someday meet the author and return the diary.

He sheltered it for 37 years across the battlefields of Tunisia, Sicily, Italy and at home in the United States (1943-1980).

Both the author and guardian die in 1980 unaware of each other’s existence.

Upon the guardians passing, the diary changes hands. The wishes of the guardian for the return of the diary becomes, for 14 years, the responsibility of the guardian’s son who wants to fulfill the wishes of his father.

A reading of the diary by a Rotary Exchange Student from Germany in Alamogordo New Mexico sets into motion the return of the diary to the wife of the author.

The diary went home in 1994 and became a touchstone to the past that would connect the wives of two soldiers from different countries sharing qualities of humanity that unite us.

The story of the diary is a story of the journey to find our better selves.

The journey of the diary is told in three parts.

The Beginning follows the diary as it accompanies the author and guardian in war time up to their deaths in 1980.

The Search recounts the efforts to find clues that would uncover the identity of the author and find the woman named Marli. It has yet to be written.

The Ceremony tells the story of the return of the diary to the wife of the author in Hameln Germany in 1994. It is yet to be written.

The thoughts written by the diary’s author are translated from German to English by our former exchange student. This translation is provided in the blog section titled The Diary.

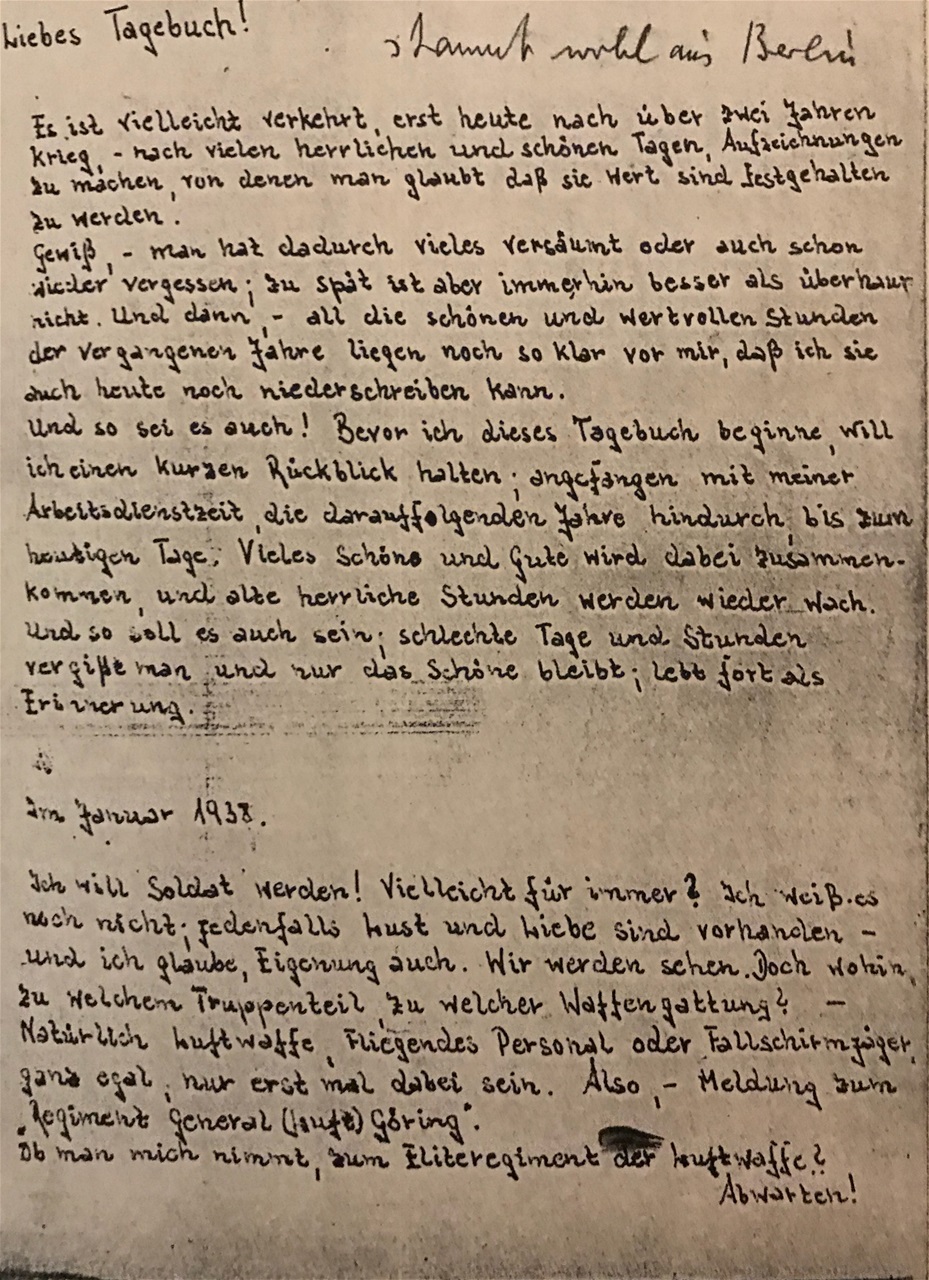

The war has been underway for two years as the author merges the past with the present. He begins to write the diary in 1942 by thinking back to 1938 when he made the decision to become a soldier.

Written information related to this story are provided in the blog section Letters and Speeches.

The Beginning

1938

I want to become a soldier!

It is January: The story of the diary begins with this powerful declaration of dedication and loyalty to country: I want to become a soldier! The author is 20 years old.

He responds to the call of duty by applying for admission into an elite Air Force Regiment led by General Hermann Göring.

February 1938: Berlin. The author joins 138 hopeful candidates for visual and physical examinations designed to select men of the highest caliber and top physical condition for admission into Regiment Hermann Göring.

Called to attention, the regiment commander Major Walther Axthelm visually examines each applicant and dismisses forty applicants using his “penetrating” eyes. Many more are rejected during the medical examination despite the author’s observation that they are “tall and strong.” And some may have been rejected by the commander who “asks a lot of weird questions.” The author has an epiphany, “Ah, he tries to figure out how I tick.”

Introducing a spark of humor into the experience, the author refers to the commander as “Axehelmet. Humor? Perhaps.

In part, the selection process uses the following criteria in deciding who is accepted or rejected into the elite regiment: eligible and fit for military service, German citizenship, between 18-25 years old, minimum of 5 foot 6 inches tall, Aryan ancestry, unmarried, no police record and confirmed support for the National Socialist State.

77% of the hopeful aspirants are rejected. The author passes all of the tests. He is accepted. Feeling happy and lucky he signs the acceptance form and is scheduled for basic training in the fall of 1938.

But first, compulsory six month service in the Reich’s Labor Force (Reichsarbeitsdienst; RAD).

The RAD was established in 1935 to militarize the work force, ease the effects of unemployment and indoctrinate participants with an ideology that would internalize the support and cohesion required for the success of young men entering military service. The work force supplied labor to various civic and agricultural projects.

March 12, 1938: The Author is silent about the “Anschluss.” However, during a visit to Austria the author reports that he and his fellow Reich Labor Service participants are enthusiastically welcomed. One can only imagine the pride felt by the author as a German as he prepares for military service. The first domino in Hitler’s plan to bring ethnic Germans outside of Germany into the “Greater Germany” begins. Faced with an ultimatum of agreeing to annexation or invasion, the Austrian President tells citizens he approves the takeover of the government to avoid fraternal bloodshed. He resigns and a Chancellor is appointed by Hitler. Austria is now “Heim ins Reich.” Home in the German Empire. Austria is but one stepping stone in Hitler’s desire for more living space (Lebensraum) and hegemony.

Click here for a more detailed examination of the historical roots of the Anschluss

October: The Author fondly reminisces the happy halcyon days of participation at construction sites, marching, drilling, sports, singing and bonding with fellow members. Living in barracks it was not uncommon for recruits to work 76 hours a week.

Esprit de Corps, camaraderie and pride are palpable in the descriptions of associations and activities the author provides.

Cohesion, support for one another, sense of unity are described as the months carry the author nearer to enlistment and training in Regiment General Goring.

The RAD provides the author with the opportunity to crystallize and align his values, experience unity of common interest and purpose and receive confirmation of leadership skills he can build upon that will be useful in the military.

Behind the enthusiastic thoughts of the author the invisible hand of the designers inoculate young men with the values and behaviors important for cohesive and loyal military service.

In October he writes "Who can forget the time we labored on the construction site, one helped the other because he needed support." Marching in full sun "the many kilometers back like a defeated army, but also in goose step." Marching in parade, engaging in sports, singing together in the evening, standing guard, and the time when "[We] painted the town red."

Indeed. Who can forget.

“Dismissal. A great time is over.” He tells the diary he and his comrades will not forget the good times-“They were just too good.”

The diary remembers the good times and much more. We will follow the author using his thoughts and comments as a road map of a soldier at war and a man in love.

He is now ready to become a dedicated and worthy member of Regiment General Goring. His Life is filled with potential.

1939

Spring

In March, the author’s battery is assigned to the forces invading Czechoslovakia with the mission, as the author explains it, to “get Prauge under control and establish order.” Perhaps unbeknownst to the author, there is more than a tactical purpose to their mission. For Hitler it is an antecedent that has a darker purpose for many people who call Czechoslovakia home.

On the drive from Berlin he notes the cold, icy roads and snowfall. The drive worsens and the author tells us, "The drivers do not yet have driver's licences, we haven't shot a single bullet yet and we go to war anyway.” We are told by the author the mission goes well; however not everyone is welcoming. ”We are welcomed with enthusiasm in the Sudeten German area, in Prague people are against us with clenched fists.”

To understand the welcome in the Sudetenland German area we take a diversion to the past: On September 29, 1938 Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy mutually agreed to provide "cession to Germany of the Sudeten German territory of Czechoslovakia.” Hitler uses the pretext that German speaking citizens of the Sudetenland area of Czechoslovakia are being oppressed. Although not party to this dismemberment, Czechoslovakia relents to diplomatic pressure and approves the annexation of the Sudetenland to Germany-an area of western Czechoslovakia inhabited by more than three million mostly German speakers. They are filled with gratitude.

March 1939. Sudetenland Germans enthusiastically welcome the soldiers on their way to Prague. The Hitler salute is omnipresent.

In Prague a different story. Many people in Prague are stunned and angered by the invasion. Hitler’s promise that he was only interested in protecting the Sudetenland Germans and had no further territorial claims was a lie.

He invades Prague. The author calls it war.

Under threat of flattening Prague, the invasion of German troops is approved by the Czechoslovakian president who places the fate of the Czech nation into the führer’s hands. Czech radio broadcasts ask citizens not to resist the German army. Bullets not required. Military resistance is minor.

Hitler announces Czechoslovakia is now part of the Greater German Reich as a Protectorate. The Czech President is a figurehead with no power to interfere with government operations not approved by Hitler’s representative.

The author reports “after a few weeks everything in Prague is streamlined after German patterns. Glorious days it was to be, everything is very inexpensive, cake, beer and food are excellent. Then we have to return.”

It is Easter 1939. The author returns to Berlin mission complete.

In the shadow of glorious days and completed mission something very ominous has been unleashed.

With the benefit of history we see the Protectorate as a euphemism for exploitation and worse.

The Nazi inquisition begins. Jews and other undesirables are removed to concentration camps. Czechoslovakian Wealth is plundered by Germany. Manufacturing companies are moved to Germany. Some are converted to make war materiel for Germany. The currency is manipulated leading to shortages in Czech consumer goods. The living standards of the Czechoslovakian people decline precipitously. They are now a people without a country.

It gets worse. We skip briefly but tragically to 1942. In reprisal for the assassination of SS Reinhard Heydridge in Prague, a wave of reprisals including the destruction of two villages and the mass killing of three to five thousand civilians occurs. Women and Children are transported to the gas chambers.

The Nazi’s will continue to protect Czechoslovakia with six long years of oppression.

The diary now leads us from Czechoslovakia to Berlin. We apprehensively follow.

Click here for a more detailed description of the acquisition of the Sudetenland and invasion of Czechoslovakia.

April and May 1943

The relentless advance of the allied troops made sleep impossible for long stretches of time. Patrols to reconnoiter the enemy were long, dangerous and often. The windless moonlit nights making hazardous conditions for locating the enemy without being shot. Dodging bullets and avoiding exploding hand grenades is not always successful. Many of his fellow countrymen and friends are being killed and wounded.

As the allied forces continue their methodical advance the author writes “it does not look good” and reaffirms “We know our duty...We are prepared.”

Enduring the fatigue he continues to tell the diary about his degenerating state wanting only “a change of underwear and fresh clothing.” and the relentless advance of the allied forces. He finds time to write home to Marli and his mother hoping mail will find safe passage.

The end is near.

Conducting patrols and then retreating from the constantly advancing allied troops left little time for sleep. Finally, a brief respite. Sleep.

His sleep was broken by the sound of rapid footsteps and gunfire. Many footsteps. There was an urgency now. No more rumors or half truths about the size of the advance. The sound of gunfire was close. Too close. The sound of profanity closer. The echo of English voices was real. Tommies or Yanks? Both? He couldn’t tell. ....., kommst du mit, bevor wir gefangen werden! Capture was becoming more likely by the day. Were they retreating or escaping? The difference was unimportant. Avoiding capture or death was important.

The Diary! There wasn’t time. Packed in the saddlebags on one of the motor bikes the diary would have to stay. But not for long.

The last entry in the diary is dated May 4, 1943. Active resistance in the American sector ceases on May 6. The German North Africa Corps formally surrender on May 13.

The last entry is short. They are positioned on standby and they were on patrol last night. He mentions they are expecting a severe attack and his receipt of a letter from home. “Nothing else is new.”

Somewhere between May 4 and May 13 the diary is abandoned. We can surmise the severe attack occurred and it was decisive.

In hushed tones the author and his men discuss to which Army they will offer their surrender. Unanimously, they decide to offer surrender to the American forces. 230,000 Axis prisoners of war are captured. The author is one among many. The author is moved to a POW camp maintained by the British and transferred to an American POW camp in Alabama. The war is over for the Author.

We now know the author’s name by the creative act of story telling. Soon we will unmask the name of the Guardian. Many of the participants in this story will not know the names of the author and guardian until 1994.

The guardian and his platoon continue the pursuit of war into Sicily. The Guardian has only a short time before his war ends.

Although the personification of the United States as “Uncle Sam” originated during the War of 1812, this poster was first displayed in 1916, continued in WW2 and can be found today in recruiting offices across the country. Bushy eyebrows, penetrating eyes, stern countenance, a rigid forefinger pointed at the observer and a tall top hat with a band of stars. Perhaps the stars communicate a subtext of “Your country needs you!” and the stern countenance and pointing finger communicates “Do your duty!” Uncle Sam demands patriotism for over 100 years. The guardian is one among 3,033,361 men inducted in 1942.

As the Author is moving from battle to battle in the North Africa German theatre of operations, the Guardian completes boot camp and further training in California. He joins soldiers on the east coast waiting for deployment to the invasion of Casablanca. It is 1942.

Kilroy was the person drawn as a graffiti character who participated in every combat operation during WWII. He was a super soldier who always got there first and remained as soldiers left. For many it was comforting to know Kilroy preceded them in combat and could be counted on to be ahead of the next advance.

Searching for Kilroy

The last place they saw evidence of Kilroy’s presence was in Training in the US. Where the hell was Kilroy? 1942 Casablanca. The battle lasted three days but winning was not easy. Casablanca was a part of operation Torch and should have largely been a meet and greet. It wasn’t. SNAFUs (Situation Normal All Fouled Up) too numerous to mention made military assaults instead of hand shakes necessary. Imagine that.

Venimus, Vidimus, Kilroy vicit

When at last the French offered the final surrender after surrendering and then rescinding the surrender more than once in the three day assault, the Army issued free post cards soldiers could use to write short notes home. Army censors made sure no one said a peep about the many drownings and loss of flat bottom landing crafts (LCVP) caused by the heavy Atlantic surf or the surprise resistance by the Vichy French. Armies do not willingly publicize the errors, chaos, blunders and confusion that often accompany war making. That task is left to historians. “I’m safe. We are sharing K rations with Kilroy,” or “Venimus, Vidimus, Kilroy vicit” might have made it past the censors. Dear Dad and Mom, I am safe but we almost drowned.

Censors would have expunged this for sure.

There was more to conquer. Tunisia was the next target-2000 km east.

The Diary Beckons

Tunisia. They wished Kilroy had already been here but he wasn’t. They were on their own. They approached cautiously. Master Sargent Schiers’ platoon learned the hard way. Death waits patiently for those who rush. Winning a battle and losing the war had real meaning born from experience. Methodically they advanced. Soldiers from the North Afrika Korps had withdrawn. In this small sector the advance was briefly halted. Morning would bring new plans.

On or about May 5, 1943. Morning broke. Abandoned, the Diary called to him. The saddle bags on a motor bike parked in a dry river bed captured his attention. He walked past, what for some men would be more enticing war memorabilia, to reach the saddlebags.

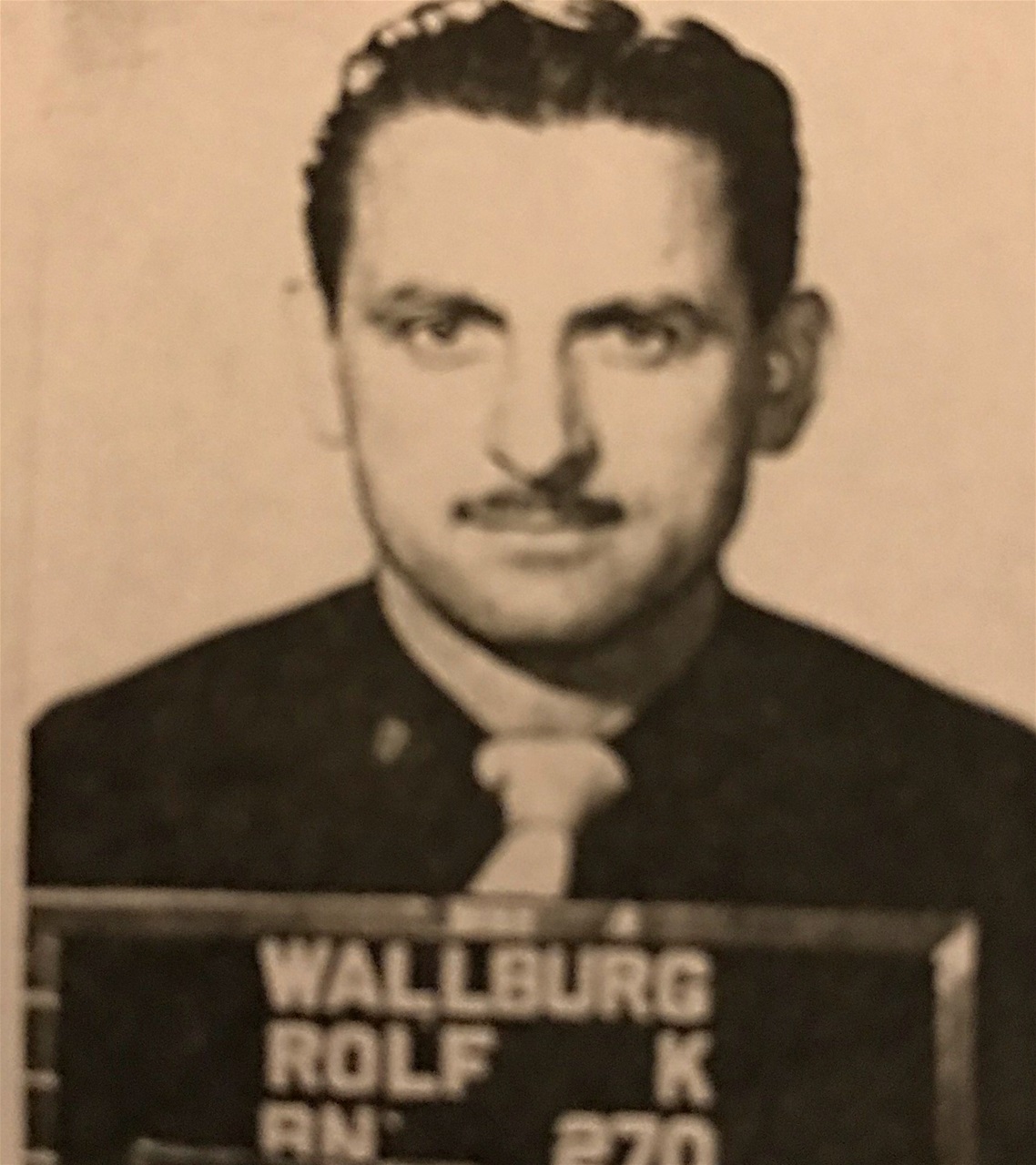

Inside, he found a red leather diary wrapped in a plastic liner. Interesting. His curiosity aroused, he wondered what would the Diary tell him about the author and his experiences in fighting the allies? What kind of a person was he? He didn’t speak or read German. He would need help in reading the story the diary wanted to tell. He packed it. He was now the Guardian. The next advance beckoned.

A detailed account of the Tunisia campaign is available at Wikipedia for the interested reader:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tunisian_Campaign?wprov=sfti1

In Italy the guardian is injured by an exploding mortar shell that propels him 50 yards in the air into a river dislocating vertebrae in the lower portion of his spine. The injury would remain with him for life. After stays for recuperation in Europe he returns with the diary to the home of his parents in Dubuque Iowa in 1944. He is released from military service January 1945, his injuries preventing him from assuming a combat role.

Robert’s father and mother Al and Edith Schiers. Albert came to the US when he was 15 from Switzerland. He served in the US Army as a corporal in WW1 completing nearly three years until his discharge in 1919. There is a village in Switzerland named “Schiers.” Mysteriously his name was Schiess before it became Schiers.

Eventually Civilians

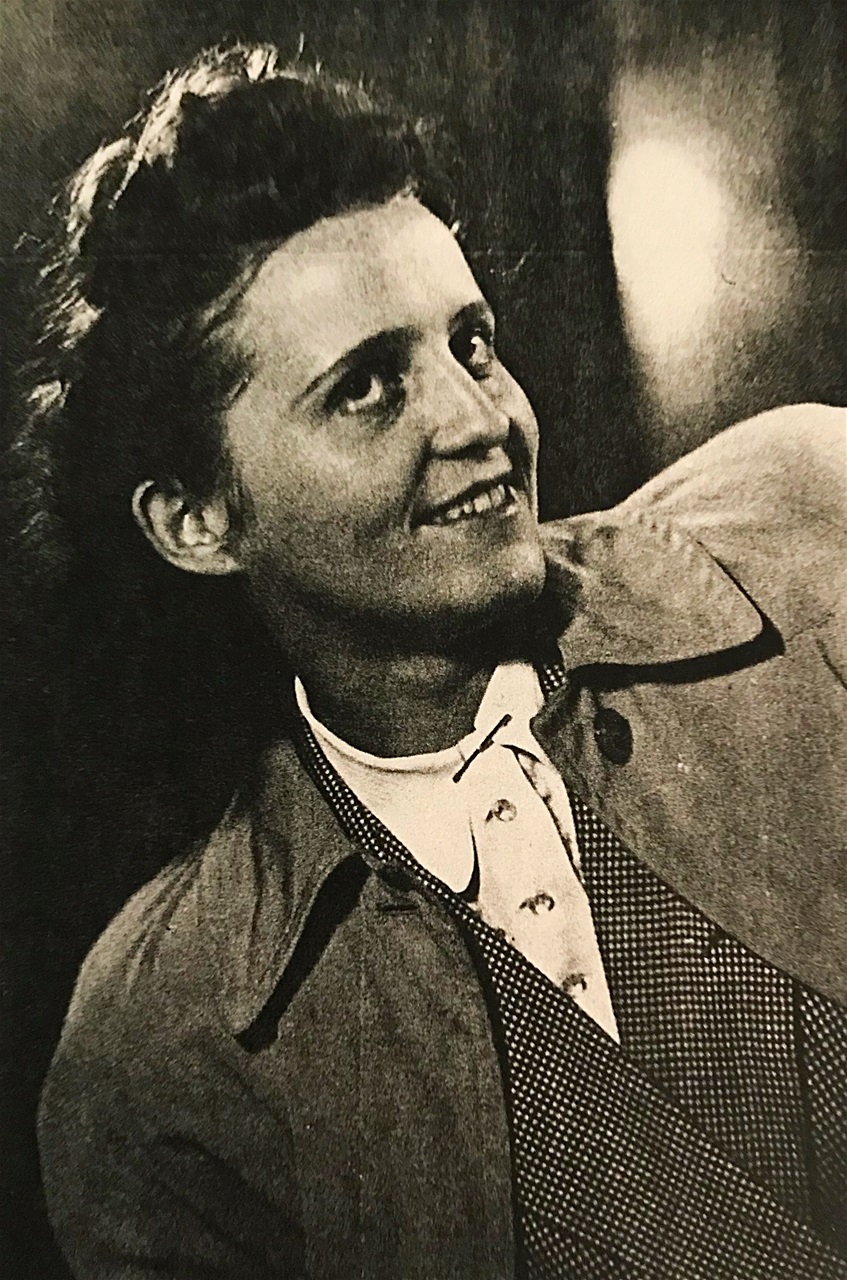

Rolf married Marli. Robert married Fran. Walburg and Schiers. Two families with a hidden bond.

On their 25th wedding anniversary Mari wrote, “We were so happily married.” Marli gave me the cuff links she gave Rolf at the Diary return ceremony. I gave them to Volker in 2013 for the part he played in the return of the Diary and our affection for him as an exchange student living with us for part of the Rotary Student Exchange Program and later as our friend.

Rolf worked as a security consultant for the railroads in Berlin. Robert as a bank Vice President. Both were happy. Navigating life’s challenges and vicissitudes they ambled forward. Life was good.

Immediately after the war there was an urgency to solve the mystery, however, over the years, the diary was presented to others for assistance less frequently. Efforts to enlist the aid of the Red Cross dropped. German speaking friends, acquaintances and business associates reduced to only occasional relationships as family and career became more important.

Rolf and Robert die in 1980.

Throughout the lifetime of the author and guardian the clues to solve the mystery remain undiscovered.

It is a mystery, as we read the diary today, that the author was not found during his lifetime.

The author’s name and last name of the woman called Marli are not provided. The name “Marli” is, as one German newspaper put it, a “needle in the haystack.”

However, Last names of real people are written in the diary. At least one of those mentioned attended the ceremony to return the words of her husband to “Marli.” Clues were scattered throughout the author’s written comments. Somehow they were missed by those who had the opportunity to read the diary on this side of the Atlantic.

We are fortunate to read this diary and participate in it’s journey. It should have been confiscated, destroyed and the author shot.

Conversations with former officers of the North Afrika Korps are chilling: “The diary was illegal. If caught he would have been sentenced to death.”

The search for the author began with hope in 1943, seeking the light at the end of a long tunnel of time and distance.

It stayed in Iowa until 1980, lived briefly in Illinois and then New Mexico until 1994.

Memories From The Past

Found in 1942, it was returned to the wife of the author in Germany in 1994. What happened in those 52 years?

As children growing up little was spoken about the Diary however there were times when visitors to our house had accents we did not recognize as the adults sat in the living room-a sacred place for adults and for children only on thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. I think these meetings support my mother’s claim that My father invited German speaking people to read the diary and see if there were any clues to help him find the author. She also told me he contacted the Red Cross on at least three ocassions seeking assistance. Once he showed the Diary to a Red Cross representative. Each time he was told it was impossible because of post war chaos and lack of clues. There was a clue but many who examined the Diary missed it.

One day when we were young children My father showed my brother Bob and me the items brought back from Germany: a German Luger, leather holster and hand grenade, and Natzi Ceremonial Flag. I can not clearly remember seeing the Diary. The gun and hand grenade remain etched in memory. Although I do not remember the words spoken, this was a solemn ocassion with my brother, myself and father. The gun and hand grenade disappeared over the years. The Diary remained tucked in the closet underneath packaged shirts waiting for rotation into active duty.

I have little information about the life of the Diary until the fateful day I showed the Diary to our exchange student Volker whom we shared with the Hanson family in Alamogordo New Mexico.

My mother told me that from time to time he told her he would really like to meet the author.

I wish this meeting would have happened. With the animosity of the war behind them, I agree with Captain Gerhardt in his observation that although they were enemies they shared a belief that the enemy was a human being (See Letters and Speeches). This shared belief in humanity from the bloody battlefield soil are the roots of the nascent relationship that would have formed.

I believe The author and guardian would have approached each other in thankfulness, empathy, discovery, respect, camaraderie and an awareness that deep below their conscious thinking something rich and deep was using the Diary; calling them to together in this moment of time to celebrate and reflect upon what it means to be truly human. Leading with their hearts we would have gratefully followed. Together we would have briefly looked into the soul of humanity. Perhaps this is one of those times life would have shown us what it wants to be if we will just let it. Perhaps.

My experiences with the written memories shared about these men from participants, newspaper articles and personal relationship with my father convince me both men shared the qualities of valor, compassion, respect for others and dignity.

I would have given much to see and experience the first gaze these two men had of each other and their first moves to what I believe would have resulted in a life long friendship. I would have been one of many to shed tears of joy and awe.

Life went forward on both sides of the Atlantic. And so must we go forward in the past.